Interventional Care

We notice that you are visiting us from . This site only services US-based visitors. Would you like to visit the site that is appropriate for your location?

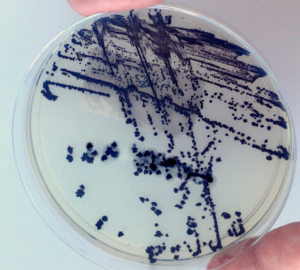

Healthcare workers are hypersensitive to the dreaded words, Clostridium difficile (C. diff.). Like a category 5 hurricane, its impact can be devastating in the healthcare environment. With a steadily rising global incidence of infection and subsequent increase in mortality, C. diff.is recognized as one of the most important pathogens in hospital and community healthcare settings. [1, 2].

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has assigned C. diff. as an urgent threat because of its association with antibiotic use and high [rates for] mortality and morbidity [3].This spore-forming bacteria, causes inflammation of the colon (colitis), watery diarrhea, fever, loss of appetite, nausea and abdominal tenderness (4) When a patient presents symptoms, extra caution is taken to observe, test, isolate or cohort, enhance cleaning/disinfection practices [or procedures] and keep fingers crossed that it won’t erupt into an outbreak. Yet transmission of C. diff. still occurs. One begins to question: What may have been missed? Have all contributing factors been considered? Could it be hiding in plain sight? Could asymptomatic carriers be spreading infection?

C. diff. Carriage

Asymptomatic C. diff.colonization (carriage) is the condition where C. diff. is detected in the absence of symptoms of infection. However, asymptomatic C. diff.colonized patients potentially act as an infection reservoir and may present a risk to others [5, 6]. The number of colonized patients is higher than symptomatic CDI cases among hospital patients, particularly when disease is endemic [7–9]. The prevalence of asymptomatic C. diff. colonization varies depending on a number of host, pathogen, and environmental factors. The prevalence of asymptomatic C. diff. carriers also varies widely within different groups. Healthy adults have been identified as being colonized at a relatively low rate without clinical signs of C. diff.(10).

Reducing Exposure

In hospitals and long-term care facilities, an increased exposure to C. diff. can be found due to high C. diff.contamination on surfaces and medical devices and on the hands of health care personnel. Infected persons or individuals with C. diff.colonization have the potential to carry disease and be a risk factor for themselves and others.

The CDC provides guidance on management of patients with C. diff.infection (11):

However, the management of asymptomatic carriers is not as well defined. Of course preventative measures such as robust antibiotic stewardship programs, strict hand hygiene initiatives and daily environmental cleaning and disinfection are non-refutable. Is it time, however, to institute a sporicidal disinfectant into the daily cleaning and disinfection of all touchable surfaces to cover for potential C. diff. spores? Such a product would need to be compatible enough to be used every day and strong enough to thwart the potential transmission of C. diff.There is much interest in the availability of standardizing disinfectant products hospital wide. With the hidden threat of spore shedding from unknown carriers, the standard product would need to be sporicidal.

Asymptomatic C. diff. colonization and its impact on the development of C. diff.transmission and infection has opened the doors for discussion, debate, and further research on the role of a non-bleach sporicidal agent for daily disinfection. Additional studies are needed to investigate the effects of such a product within healthcare, however, the future seems very promising.